Helen DeWitt ate my newsletter.

Rereading The Last Samurai, and some thoughts on what makes a life worth living.

I fully intended to send out this newsletter in the first week of August, and then the second week of August. It kept not happening. There are external factors: I was preparing my children for seventh and tenth grade, planning my daughter’s bat mitzvah, winding down a job that I’ve had for 11 years. Here in Austin, we’ve had a week of temperatures over 100 degrees. It never really cools down at night. The air is thick and sluggish, even at 7:30 a.m. In the afternoons, I feel about as sentient as a lump of dough. It doesn’t help that my 48-year-old body has some kind of inner heat lamp that goes on and off, of its own accord, at random intervals throughout the day and night.

In her essay, “Against August,” Haley Mlotek (according to the author’s Instagram, it’s pronounced “melodic”) makes my point for me: “In August I cannot think, so I cannot work.”

Physically, August is a slog. But unlike Mlotek, I do not oppose August. August is the last gasp of summer. It feels like death, but it sets the stage for resurrection, a new school year, the Jewish high holidays with their promise of apples and atonement. August is shavasana. I’m not listless; I’m in a state of suspended animation.

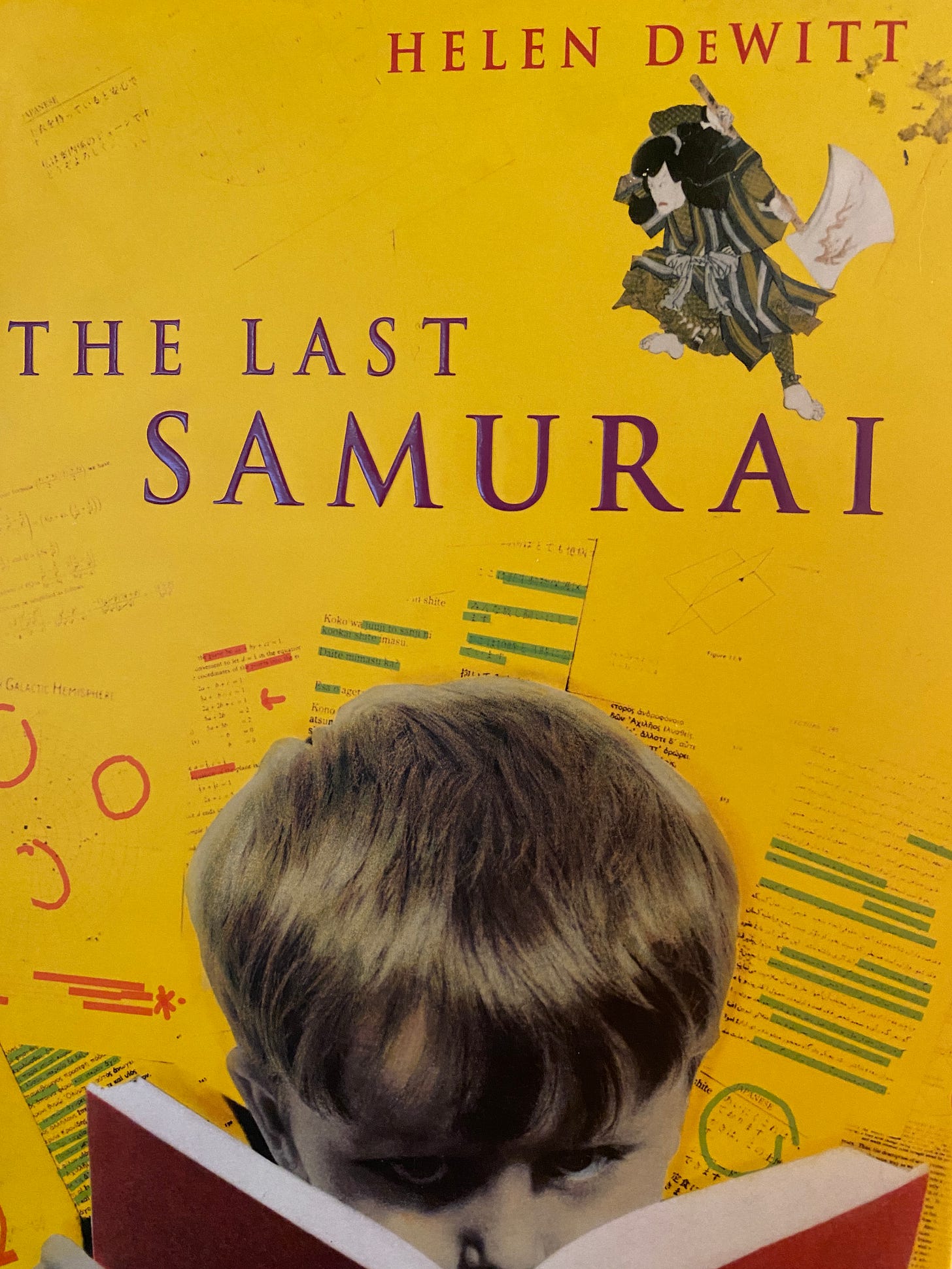

There is a stack of promising unread novels in the living room; earlier this month, I thought I would write about one of them. But after weeks of avoiding their side-eye as I passed them on my way to flop on the couch, I decided August was not the month for new things. Instead, I reread one of my favorite novels, Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai.

The Last Samurai, which was first published in 2000, is the story of Sybilla, a single mother who was born in America but lives in England, and her son, Ludo, which is not the name on his birth certificate. Sybilla is not the kind of woman who cares about official birth records or compulsory education. Having studied classical languages at Oxford, Sybilla educates Ludo like John Stuart Mill was educated by his father. (An education described in Mill’s Autobiography.) She teaches him Greek at age four, and it turns out Ludo is a child prodigy, gifted not only in languages but in math and science. He demands that Sybilla teach him other languages, many of which are reflected on the page. The Last Samurai includes passages in Old Norse, Inuit, Hebrew, Arabic, and Japanese. (Apparently, the diversity of fonts and alphabets led to considerable conflict in the novel’s publishing process, including a battle with a copy editor in Wite-Out!)

The Last Samurai begins with a narrative from Sybilla’s perspective, interrupted frequently by Ludo’s all-caps pleas to learn Japanese and questions about the plot of Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, which Sybilla and Ludo watch repeatedly because Sybilla hopes the movie will provide her son with male role models.

On the page, this looks like a hybrid of Sybilla’s thoughts, Ludo’s precocious interruptions, and clips from Seven Samurai.

I tell L that I have to go downstairs & put the heater on to type, & that he will have to stay in bed and watch the video. Of course he instantly begs to come too. I say You don’t understand, we need £150 for the rent and £60 for the council tax, that alone is £210 and as you know I made £5.50 an hour before tax, 210 divided by 5.50 is approximately 40—

38.818

38.818, fine

18181818181818

the point being

1818181818181818181818181818

That if I work 10 hours a day for the next 4 weeks I can get the disks in Monday, we’ll get the cheque on Friday, and we can pay two bills, and if we stretch out the £22.62 we have in the house we can also buy food

The master swordsman isn’t interested in killing people. He only wants to perfect his art.

I can’t work with you downstairs. I know you don’t mean to distract me but you do.

I just want to work.

Yes but you always ask questions.

I promise I won’t ask questions.

That’s what you always say. You stay here and watch Seven Samurai and I’ll go downstairs and do some work.

NOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

About halfway through the book, Ludo takes over the narrative. He has always wanted to know about his father, a writer with whom Sibylla had a one-night stand and who knows nothing about his son’s existence. (Sibylla refers to the man only as Liberace because of his sappy writing.) The novel becomes a quest, resembling the structure of Seven Samurai. Ludo, who is 11 years old now, confronts seven potential father figures.

You could say The Last Samurai is about a mother trying to raise her rare and precious child. You could say it’s about a child trying to save his rare and precious mother. In both cases, The Last Samurai is concerned with what it means to live a worthwhile life—which for Sybilla means a life of art and ideas, buttressed by grand gestures and infatuated with language.

I love so much about this novel, but the part I love best is how DeWitt depicts love of language. Take, for example, Ludo discussing his favorite Arabic verb:

[H]ere is a triliteral verb in which all three letters are ya; a verb which only occurs in Form II, with the middle ya reduplicated (unfortunately this means the final ya is then written alif, but you can’t have everything); a verb which means ‘to write the letter ya’ (Wright) or ‘to write a beautiful ya’ (Haywood and Nahmad)! This has got to be the best verb in the language—and Wehr doesn’t even bother to put it in the dictionary!

In my twenties, when I was a grad student in Slavic Languages and Literatures, I spent my days reading Russian novels, fragments of Old Church Slavic, and 19th century Polish plays and poetry. I had my own study carrel, a tiny metal cage on an upper floor of the library at the University of Wisconsin. I spent hours in that weatherless environment, staring at photocopies.

My Russian was pretty good, but reading old Slavic and Polish was a laborious, bottom-up process. I decoded one word at a time, annotating heavily, marking each line with a check mark when I had read it. Back then I mostly wore turtlenecks and denim overalls. In my language-induced stupor, I would forget about the tools that I stuffed in the front pocket of my overalls. When I got up to pee and dropped my overalls in the bathroom, everything would spill out—pens, pencils, and highlighters crashing on the tile floor and rolling to distant corners beyond the stall door, the clatter bringing me back to my senses.

DeWitt, like Sybilla, studied classics at Oxford and understands this type of scholarly obsession. She writes of one character: “He was a linguist, and therefore he had pushed the bounds of obstinacy well beyond anything that is conceivable to other men.”

There is a recurring motif in The Last Samurai of a person doing a thing over and over again. Sybilla watches Seven Samurai. Sybilla’s mother plays Chopin’s Prelude No. 24 in D minor, “a bitter piece of music which gains in intensity when played 40 times in a row.” In the winter, Sybilla and Ludo flee their frigid home to ride the Circle Line for days on end, providing the opportunity for a straw poll of London commuters’ opinions on the merits of teaching a child to read ancient Greek.

Amazing: 7

Far too young: 10

Only pretending to read it: 6

Excellent idea as etymology so helpful for spelling: 19

I noticed these circular patterns more on my rereading—probably because I was treading on familiar ground.

Some people love to reread. There are writers who reread their favorite novel as a kind of ritual (see Rebecca Mead on Middlemarch). Children are incredible rereaders. I am pretty sure that as a child I read A Little Princess a billion times. (My favorite scene was the one in which Sara Crewe proves to the clueless headmistress that she can speak French.)

As a group, adults seem to be afraid of rereading for the same reason that too often prevents them from reading novels in the first place: fear of wasting time.

Rereading is risky. I have this sense that my enjoyment of certain novels will not survive a second engagement; to avoid disillusionment, I leave them on the bookshelf of my memory, where they can remain beloved. On the rare occasion that I have dipped into books that I once loved, I’ve often found that my dread was well-founded. But it never felt like a waste of time. I read as much as I wanted and put the book down with a little chuckle at my younger self. I’m never a martyr about finishing books, but there is certainly no need to finish a reread; I have read snippets of Tropic of Cancer, Breakfast of Champions, The Secret History, Possession, and The Catcher in the Rye and stopped as soon as my eyes started to skim, confident that I got the gist. When I find a book that stands up to rereading in its entirety, I pay attention. There’s something to be learned. When I love a book at two different ages, it says something about who I was then, who I’ve become, and what different times in my life have in common.

When I find a book that stands up to rereading in its entirety, I pay attention. There’s something to be learned. When I love a book at two different ages, it says something about who I was then, who I’ve become, and what different times in my life have in common.

I read The Last Samurai for the first time in 2001, right after leaving graduate school. I had followed a boyfriend to New York, where I was working at a literary agency and contemplating returning to a PhD program in English or library science. That carrel at the University of Wisconsin was fresh on my mind. In the end, I opted not to stay in publishing or return to the metal carrel (my version of the ivory tower.) I was tired of reading for someone else’s reasons. Instead, I chose law school. In the law, I figured, at least my reading life would be entirely my own. The first time I visited my law school, it was pretty clear I’d left academia. The student tour guide didn’t bother walking us through the library; she just waved in its general direction and said: “We’ve got carousels!”

Sybilla would like a word here:

There are people who think contraception is immoral because the object of copulation is procreation. In a similar way there are people who think the only reason to read a book is to write a book; people should call up books from the dust and dark and write thousands of words to be sent down to the dust and the dark which can be called up so that other people can send further thousands of words to join them in the dust and the dark. Sometimes a book can be called from the dust and the dark to produce a book which can be bought in shops, and perhaps it is interesting, but the people who buy it and read it are not serious people, if they were serious they would not care about the interest they would be writing thousands of words to consign to the dust and the dark.

There are people who think death a fate worse than boredom.

In my twenties, when everything in my life felt up in the air, my definition of a worthwhile life was not too different from Sybilla’s: reading what interests me because it interests me and avoiding boredom. Twenty-three years later, I am in another liminal state, but my definition of a life worth living hasn’t changed much. I’m leaving a legal job that has become boring, and I’m still committed to reading (and now writing) what interests me because it interests me. It’s no wonder The Last Samurai was calling to me from the shelf.

The boyfriend I followed to New York in my twenties worked as a server in a Spanish restaurant on the Lower East Side, but he had an MFA in film. After the first time I read The Last Samurai, I told him I was interested in Kurosawa. “OK,” he said, and went off to do something to the Netflix queue. (Remember those bygone days when you could only have three red-sleeved discs at a time?)

We watched Japanese movies for the next two years. By the time we’d run through the canon, I thought I was beginning to understand Japanese. (I wasn’t. I am not a prodigy like Ludo. However, my brain was permanently re-programmed to read the English word “sake” as an alcoholic beverage made from fermented rice.) Luckily for me, I had found someone whose idea of a worthwhile life was compatible with mine.

The other night, when I opened (with an audible crack) my hardback first edition of Seven Samurai, out fell a flyer for LIVE FLAMENCO on Sunday nights at my boyfriend’s Spanish restaurant. “Look!” I said, to the man on the other side of the bed who gave me that flyer and two years of Japanese cinema. I hope we get to watch Seven Samurai with our children soon.

Let’s end with the words of Hilary Mantel in the Guardian: “Rereading is a pleasure and duty of middle age, and illuminating, even if it only sheds light on how you yourself have changed.”

As I get older, I’m more interested in rereading. What would I learn if I devoted every August to rereading? I might not wait that long.

Other interesting things

I cannot leave DeWitt without alerting you to her second novel, the hilarious, insanely satirical workplace sexual harassment comedy, Lightning Rods. Please take a look at DeWitt’s official website to get a sense of how unlikely it seemed as a follow-up to The Last Samurai—a publishing sensation, despite the Inuit and Old Norse. There’s a reason Lightning Rods made the Slate/Whiting Second Novel List. Dan Kois called the book a “demented comic masterpiece”: “Lightning Rods is an immodest proposal: a sex comedy that pursues a single dirty joke much, much further than it ought to and, in doing so, skewers American capitalism with a purer, more invigorating hatred than any novel I can remember.”

I love this profile of DeWitt by Christian Lorentzen in Vulture: “Many, many writers are chronically broke. Many have a long list of grievances with the publishing industry. Many will tell you about the circumstances that would have allowed them to enjoy the success of Ernest Hemingway or David Foster Wallace. Many have had multiple brushes with suicide, but there’s only one who wrote The Last Samurai and Lightning Rods, two of the finest novels published this century, and she’d recently spilled a glass of iced tea on her MacBook.”

This week in Electric Lit you can read interviews with three short story authors about the books and stories they reread over and over again. Here’s Jamel Brinkley on chain-reading Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison: “I was a sophomore or junior in high school and I would literally get to the end of that book and then start it immediately over again. I did this multiple times, so much so that my mom thought something was wrong with me. Something about that obsessive rereading still guides me.”

How funny, having never read The Last Samurai—likely because the title conjured up images that were not that interesting to me—the other day in the NYT I read about a woman who has just finished reading it and who waxed prosaic about it at length... which of course means my interest is now piqued and I will have to read it.

I am not a big re-reader, though there are a few books I like to return to again and again. Madness, Rack, and Honey by Mary Reufle always grounds me in a particular way, as does Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (a book I have given away so many times that I am probably on my 6th or 7th copy). I've read A Confederacy of Dunces an embarrassing number of times, which is weird because I'm not a huge reader of absurdist humor, but it still makes me laugh out loud, 30+ years after the first time I read it.

Around Easter this year, I wandered into a second hand book store in one of our bigger local village and had a wonderful conversation with the owner about American Politics. I had decided I should try to read some fiction in French, and the first thing that jumped into my hands was a copy of Ray Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles, a collection I must have read about 35 years ago, when I was 10-years-old or so. It seemed sensible that my first science fiction author should also be my first novel read in French. (I've tried reading Antarctica by Claire Keegan in French, side by side with the English version, but it didn't stick). So here I am, re-reading The Martian Chronicles. I am an inveterate bathtub reader, so I don't have a dictionary or translation app at hand, and have mostly muscled through, reading under my breath and missing at least 10 percent of the florid adjectives and verbs. But I am getting through it, and following each story as rapt as I did the first time around.

What shocks me about this experience is not that I remember the stories precisely or anything, but rather that I remember the feeling so many of these stories evoked the first time I read them. There is a certain poignant sadness and injustice and sometimes wry humor in the first handful of stories and I FEEL similar sensations to my childhood readings and that fills me with an eerie delight.

I wonder how many novels I would benefit from re-reading in French?

Your Polish/Russian forays are impressive. Ambitious. Unimaginable.

Love that you write about reading. It's such a pleasure to see you land in my inbox.

I skimmed over much of this one because Samurai is next on my queue. I knew you loved it but I hadn't cracked it til recently, using the Books app on my iPhone (one of, along with voice memos, the best reasons for the iPhone to exist), which I used to sample lots of the books from the NYT's top 100. Yeah, that voice, immediately. Looking forward to circling back to this post after my *first* reading.