There was a time, when I was younger, that I thought I had to ruthlessly block out the side of me that always knows what’s in the pantry in order to get any writing done. Now I think it’s pointless to reject domesticity as a source of creativity. The only way out is through.

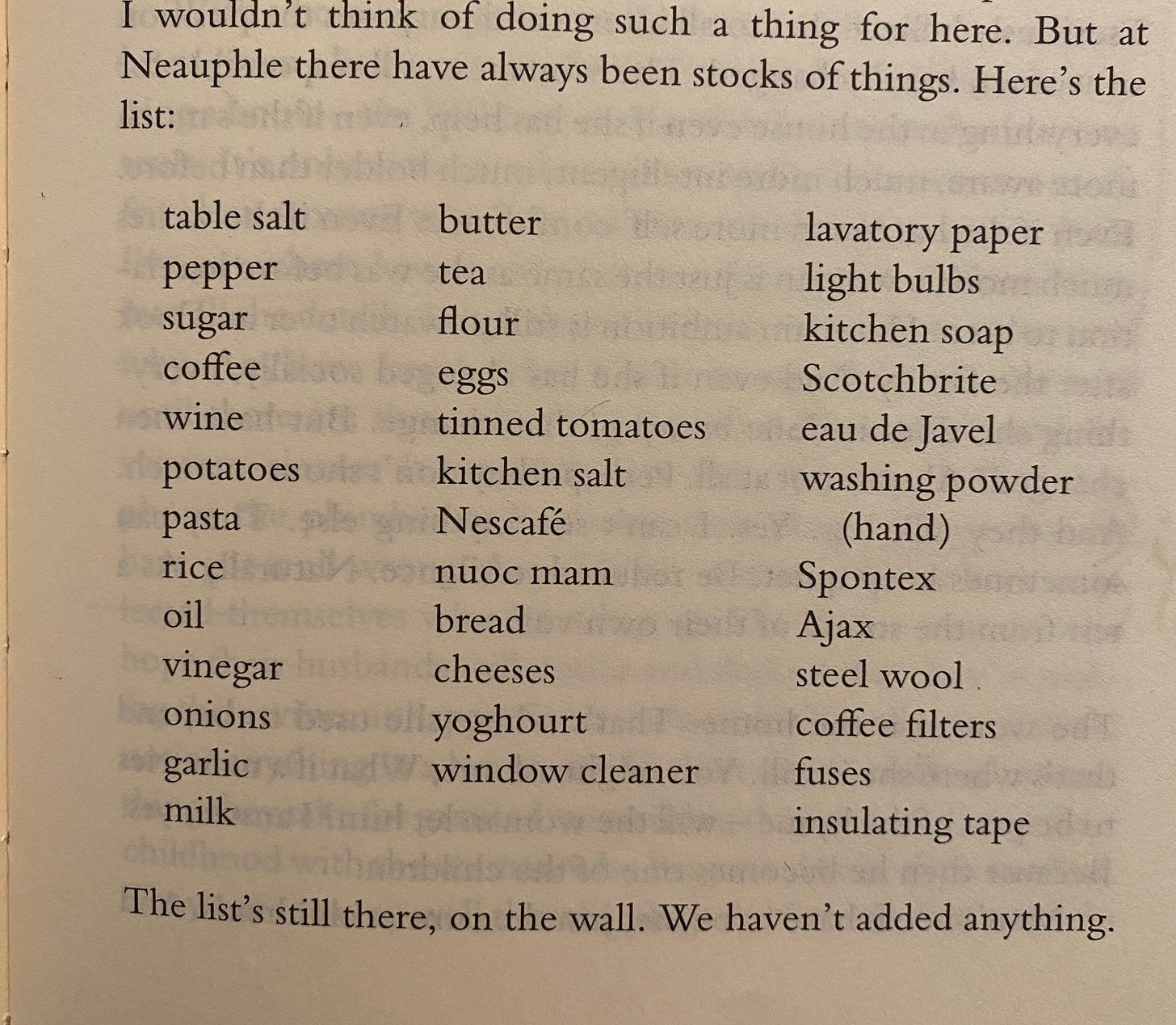

I was thinking about all this while reading Practicalities—a collection of short transcribed conversations with Marguerite Duras. In a chapter called “House and Home,” Duras recites a list of 37 necessities that she kept on the wall of her house in Neauphle-le-Chateau, where she lived and worked in the 1960s and 70s. I loved that she was still talking about this list twenty years later. The list seemed to represent something essential about Duras herself—and I began to wonder what it meant for me as another woman who writes in a house where I live with my family.

Who is Marguerite Duras?

Marguerite Duras (1914-1996) was a French novelist, playwright, and experimental filmmaker. Her most well-known book, The Lover, is a fictionalized account of her sexual relationship, at 15, with an older Chinese man in French-occupied Vietnam (Indochina), where she grew up and lived on and off until her twenties. Duras, which is a pseudonym, is the name of her father’s native village, near the Gascony region of France. As Rachel Kushner writes in the introduction to the Everyman’s Library edition of The Lover, Wartime Notebooks, and Practicalities:

The language of Gascon, from which this practice of a spoken ‘s’ derives, is not considered chic. More educated French people not from the region might be tempted to opt for a silent ‘s’ with a proper name. In English, one hears a lot of Duraaah—especially from Francophiles. Duras herself said Durasss, and that’s the correct, if unrefined way to say it.

Practicalities

Published in 1990, Practicalities (La Vie matérielle) consists of 48 short essays on topics such as “The theatre,” “Animals,” “The last customer at night,” and “Men.” In her seventies, Duras dictated the essays to her son’s friend, Jerome Beaujour, and they edited them together.

If you are the type of person who wants to listen to an older woman speak with authority about what she knows (I am), you might love this book. Unlike some of us, Duras doesn’t seem like she needed to age into her authoritative voice. “Her assertions have the base facticity of soil and stones,” writes Rachel Kushner, “even if one doesn’t always agree with them.” Some readers will find her pronouncements hopelessly dated or even offensive, particularly when she explains homosexuality. When she sticks to her own lane, however, she could be acknowledged as a godmother to our current age of heteropessimism:

Heterosexuality is dangerous. It tempts you to aim at a perfect duality of desire. In heterosexual love there’s no solution. Man and woman are irreconcilable, and it’s the doomed attempt to do the impossible, repeated in each new affair, that lends heterosexual love its grandeur.

So, about that list.

The 37 items that Duras considers essential relate to preparing meals, cleaning, and repairs. The list doesn’t include furniture, dishes, office supplies or toiletries other than “lavatory paper” and “hand soap.” The list does include butter, milk, eggs, unspecified “cheeses” and, in my translation, "yoghourt," but aside from potatoes, garlic, and onions there is no fresh produce, which I love: I imagine Duras cooking according to the seasons, eating salads in the spring, tomatoes in the summer, and mushrooms in the winter.

I confess to certain preconceived notions of how French women live. Even reading the chapter in Practicalities called “Alcohol,” which describes waking up every two hours at night to drink, I still imagine Duras walking briskly to the farmer’s market in the morning to inspect green beans and tomatoes with a discerning eye. And maybe she did. I used to drink wine every night, often more than was good for me. But even when I knew I was poisoning my body, I was still devoted to cooking and eating balanced, healthy meals.

Duras would disapprove of my housekeeping in many respects: she has no truck with women who tolerate clutter and don’t do repairs. (“It’s only women who are not really women at all, frivolous women who have no idea, who neglect repairs.”) I leave repairs to my husband and move clutter from the kids’ rooms to the garage, where it piles up for months before I eventually take it to Goodwill. Duras knows what’s wrong with women like me—it looks like a problem of space, but really it’s a problem of time.

Lots of women never solve the problem of disorder—of the house being overrun by the chaos families produce. They know they’ll never be able to overcome the incredible difficulties of keeping a house in order. Though anyhow there’s nothing to be done about it. That sort of woman simply shifts disorder from one room to another; moves it about or hides it in cellars, disused rooms, trunks or cupboards. Women like that have locked doors in their own houses that they daren’t open, even in front of the family, for fear of being put to shame. Many are willing enough but naïve—they think you can solve the problem of disorder by putting the tidying-up off until later, not realizing their ‘later’ does not exist and never will.

Where we’re on the same page is the pantry:

I have this deep desire to run a house. I’ve had it all my life. There’s still something of it left. Even now I still have to know all the time what there is to eat in the cupboards, if there’s everything that’s needed in order to hold out, live, survive. I too still hanker after a sort of shipboard self-sufficiency on the voyage of life for the people I love and for my child.

“House and Home” is not—I really can’t emphasize this enough—a blueprint for gender equality in household management. “A house means a family house,” Duras writes:

a place specially meant for putting children and men in so as to restrict their waywardness and distract them from the longing for adventure and escape they’ve had since time began. The most difficult thing in tackling this subject is to get down to the basic and utterly manageable terms in which women see the fantastic challenge a house represents: how to provide a centre for children and men at one and the same time.

Duras was not a feminist so much as a woman utterly convinced of the superiority of women. She seemed to view men as incorrigible children. There is nothing in that paragraph about a woman’s “waywardness” and “longing for adventure and escape.” And yet, read what comes next:

At Neauphle I often used to cook in the early afternoon. That was when no one else was there—when the others were at work, or out for a walk, or asleep in their rooms. Then I had all the ground floor of the house and the garden to myself. It was then I saw most clearly that I loved them and wished them well. I can recall the kind of silence there was after they went out. To enter that silence was like entering the sea. At once a happiness and a very precise state of abandonment to an evolving idea. A way of thinking or perhaps of not thinking—the two things are not so far apart. And also of writing.

“To enter that silence was like entering the sea.” I think of the days when I stay at home to write while my husband takes our two children to school and then stays out to work. Sometimes, after I shut the door behind them, I place a hand on my chest and take a deep breath in, as if I could feel myself inhaling the empty space. I never love my family more than in those precious first minutes of silence. I don’t stop loving them when the house is filled with their voices again, but I sometimes long for the voices to quiet down so I can hear myself think.

Restless thoughts

Earlier in my 40s, I used to lie awake at night and think about the adventures I’d had when I was younger. I wondered what had happened to that bold young woman, how I’d become so domesticated. In my mind, I replayed scenes from Vagabond (Sans Toit ni Loi), Agnes Varda’s 1985 film about Mona, a young female drifter. I’d seen Vagabond once in my twenties. I liked the movie, but it wasn’t until I was older and living in a house with two small children and a husband that I became obsessed with my memory of Sandrine Bonnaire, as Mona, walking in and out of the camera frame with a heavy backpack, smoking.

I got excited in 2021 when I heard about Dana Spiotta’s novel, Wayward, about a 50-something woman who buys an old house in Syracuse after Donald Trump is elected president in 2016 and moves into it by herself, leaving her husband and teenage daughter. I was hoping to find a fictional reflection of my midlife wanderlust. I did love every scene of the main character drinking Japanese whiskey and staring into a fire in her unheated, ramshackle house. Unfortunately, the novel also had a plot that didn’t stir my imagination like those scenes at the hearth.

This year, and maybe forever after, Miranda July’s All Fours was the most compelling novel I read about female wanderlust. I haven’t read the divorce memoirs that so many people are worked up about. As a reader, I’m more drawn to the voices of women who lived before the women’s movement of the 1970s, like Marguerite Duras.

I’m struck with how little has changed, in the domain of house and home. I’m also curious about the French perspective. I have a sense that a lot about the current strain of feminist anguish in this country is specific to living in late-capitalist, post-pandemic America.

A memory

I spent a week in Paris in the summer of 1997, when I was 21. I saw a woman on the street one day who I still think of sometimes. This woman—I would call her a “young mother” if I saw her today—was probably in her early thirties. She wore a brown dress with a yellow floral pattern and buttons up the middle, and her brown hair was curly and short. She could have been the heroine of a movie set during World War II. I was walking around by myself that day, and I slowed down to watch her from across the street. She had stepped to the side of a busy sidewalk with a cart full of groceries and was kneeling down to address a small child. Though I couldn’t follow their conversation, it was clear that the child had decided to stop walking. The woman spoke to the child in cajoling tones for a little while, and then she abruptly stood, picking up the child in one arm and the cart in the other arm, and jogged up a short flight of steps to the front door of a building, which she smoothly opened by some machinations at her hip. Her arm muscles bulged beneath her short sleeves. But she didn’t look like she was straining or angry as she and her cargo vanished behind the door. She seemed to have strength that came from her life as a mother in a city, not the kind that comes from working out in a gym. I wondered how many flights she would have to climb inside.

When I saw that woman, my highest ambition was to be a flȃneuse. I pictured myself as a citizen of the world, proficient in all the European languages—profession not specified, but something to do with words. This future version of me would while away long afternoons in sidewalk cafes, writing in her notebook, discussing philosophy, literature, and politics over cappuccino with other fascinating types. (It says a lot about my thinking at the time, that I believed a small adjustment in spelling was all I needed to move through the world like a Parisian man about town.) I did not want to have children. But when I saw that French mother on the sidewalk I thought, I want to be like her.

Parting thoughts

Last month, an essay I wrote about time and motherhood was republished in The Manifest Station, and the best thing happened: I got an email from a kind and generous reader in response. Among other things, she wrote about her impression that the rhythm of life in France is more natural than in our country. Maybe that’s it. I’m sick of the American myth of work-life balance.

Duras wrote and made films in the same house that she kept clean with Ajax and where she made soup for her family. There’s something appealing about her implicit rejection of the Woolfian “room of one’s own.” In “House and Home,” Duras writes that she’s read Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, but “I don’t have books any more. I’ve got rid of them, and of any idea of having them. It’s all over.” But she could still tell you what was on that list.

Other interesting things

The Baby on the Fire Escape by Julie Phillips is a book that I have recommended to all my friends who write while raising children. I read this collection of biographical vignettes about artist-mothers a couple of years ago, and I’m still talking to it in my head.

Here’s an article about how queer people are writing about houses, tracing the spatial metaphor from James Baldwin to Carmen Maria Machado and Yael van der Wouden, whose novel, The Safekeep, I literally cannot wait to read. (I’m running out of this coffee shop right now to buy myself a copy.)

WaPo reports that a lot of NFL players keep a journal! ““A lot of us, we feel so defined by what we do and football has been part of our identity for so long that it is kind of hard to talk to somebody or relate to somebody that really hasn’t been a part of that space,” [Commanders backup QB Marcus] Mariota said. “So being able to write those things down, to write out how you feel, to be vulnerable, I do think is important. It allows guys to get in that space where they can separate work and life.”

You can read an essay drawn from Rachel Kushner’s introduction to The Everyman’s Library edition of The Lover, Wartime Notebooks, and Practicalities here.

I love your writing, Sarah, and want to read Duras...I always feel woefully behind in my reading when I see what you're up to! I wonder if I could talk the UT football team into letting me teach their guys a journaling workshop. That' s not a population I've thought of. Cheers, Bev

Lovely.