How to Collect Words like a Writer

Gianni Rodari's "fantastic binomials," cobblery with Emily Hunt Kivel, and other thoughts about words

Today I want to write to you about words. This is the first part of a series on How to Read like a Writer.

I recently learned from the Marginalian about the “fantastic binomial,” a phrase invented by Italian children’s book author Gianni Rodari to describe his creative process. (A “binomial” is a thing with two parts, usually a mathematical expression.) Rodari explained that many of his stories were based on a combination of two words:

Any randomly chosen word can function as a magic word to unearth those fields of memory that had been resting under the dust of time… The fantastic arises when unusual combinations are created, when in the complex movements of images and their capricious overlappings, an unpredictable affinity is illuminated between words that belong to different lexical fields.

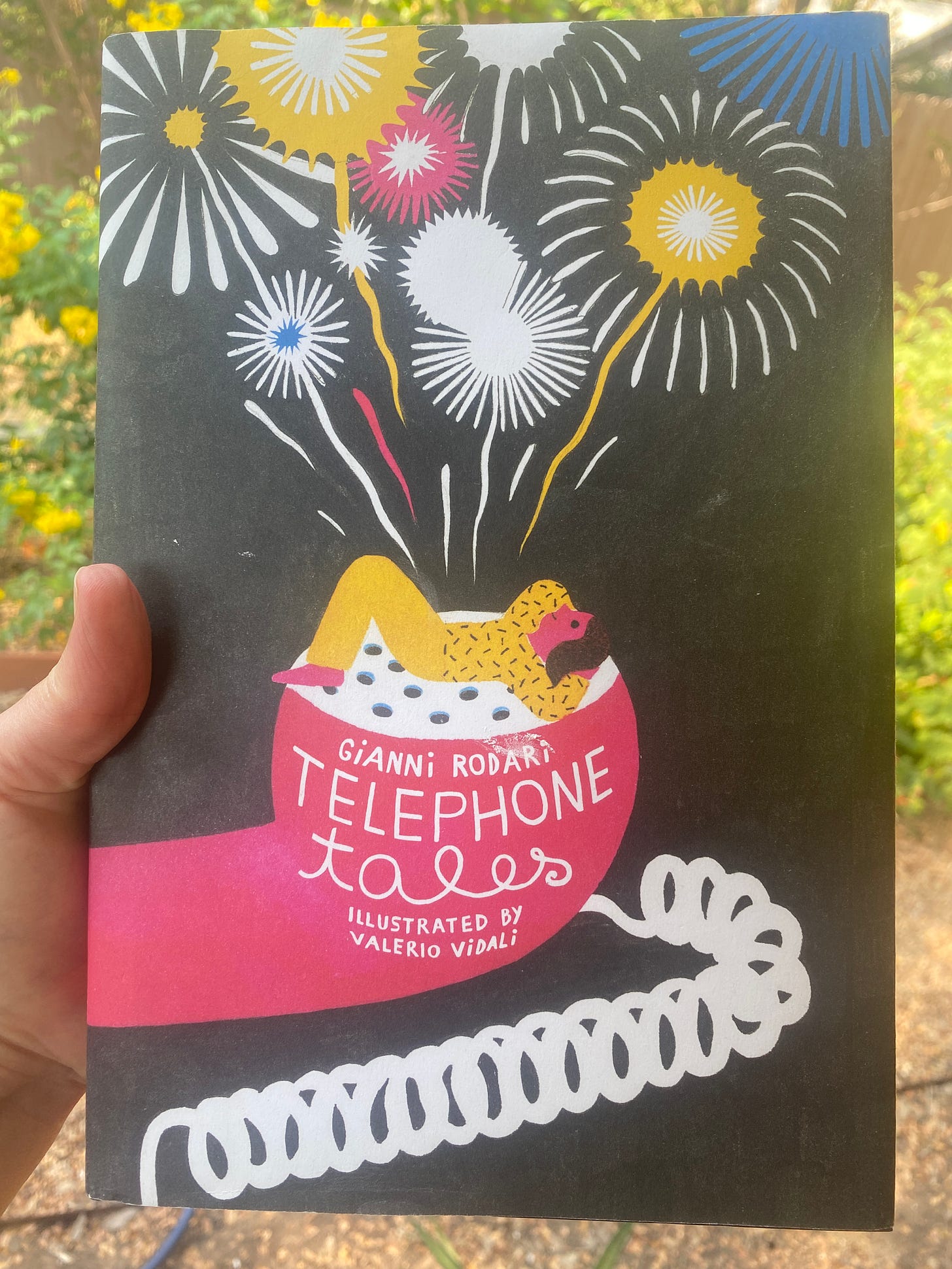

Walk with me now to the bookshelf, where we reach up to the top shelf for a hardback book with an illustration on its cover of a person dreaming on the talking end of a neon pink telephone: this beloved object is Telephone Tales, Rodari’s 1962 book of 70 stories, each short enough for a frugal Italian businessman on the road to relate to his daughter at bedtime over a payphone. The first story that I open to is titled, “A Building for Breaking.” And here’s another one called “Educational Candy.”

Other stories: “Gobbledy Fever,” “The War of the Bells.” I think you see my point.

As readers and writers, words are our raw material. You can’t build any piece of writing without them, and yet we don’t spend a lot of time focusing on the individual words that make up our creations.

If we get more granular in a workshop or a book review, it’s often to discuss a writer’s sentences: is the sentence structure grammatically correct, is it effective, is the writer varying short and long sentences for pace? There’s certainly nothing wrong with that. We might think that we don’t need to make a practice of studying words. (Presumably, this is particularly true for those of us who are native speakers in the language in which we usually read or write.) It can be tempting to focus on the more architectural aspects of literature, like plot structure, genre, and character development. But words are the building blocks. I think they deserve our close attention.

When you start to read like a writer, you will notice how the words that an author chooses give the text its texture and specificity. In Writing Down the Bones, Natalie Goldberg writes that we should “learn the names of everything: birds, cheese, tractors, cars, buildings. A writer is all at once everything — an architect, French cook, farmer — and at the same time, a writer is none of these things.”

I love it when I can tell that a novelist has taken the time to learn a vocabulary specific to her subject. For example, in this passage from her novel Dwelling, Emily Hunt Kivel describes a woman who lives in a shoe and is learning how to make shoes:

Indeed, all she thought about was shoes. She thought about the degree of step asymmetry, the degree of each arch, the wideness and narrowness, the heel depth, the toe room. She found herself stopping passersby, asking them about their footwear’s material (which they didn’t really know, usually answered in an elliptical lilt of ‘leather’ or ‘mylon?’ and the maker). The dining table in the center of the shoe’s cavernous ground floor had become almost unrecognizable, so covered with blocks of wood and ribbons of polyester and tiny hammers and sewing tools and pins and carving knives and shoes, so many shoes, leaning this way and that, in various stages of completion. In the evenings she would sit at the table, focusing on the new design at hand, until she felt Bertie’s fingers on her shoulder, pulling her to dinner or to bed. In the middle of the night, she would rise from the mattress, leave the man sleeping, and, in the dark moonlight, make her way down the winding stairs to the makeshift workshop, where she would continue to carve away at a pair of recycled cork mules.

The shoemaking words are what makes this passage so interesting; without them, we would have a more generic depiction of a woman discovering her purpose. Pay attention to the nouns: step, asymmetry, heel, toe, design, wood, polyester, hammer, carving knife. By making this vocabulary an intrinsic part of the novel, the author also gives us insight into her main character so that a few pages later, in a passage about a pair of boots, we understand the depth of Evie’s love:

He dug his toe into the wood floor. He was wearing cutoffs and the pair of boots that Evie had gifted him, over a week ahead of schedule. They had thin soles that were fortified on the inside with a pliable cottonwood. The ankles were mesh. The heel had give. You could tell, watching the man move, that he was walking confidently on air.

So how can you learn more words and deepen your understanding of the words you know?

In 5 Ways to Read Like a Writer, I described my practice for learning and collecting words as I read. My approach is based on Priscilla Long’s “lexicon practice,” which she describes in The Writer’s Portable Mentor: A Guide to Art, Craft, and the Writing Life. There are two parts to this practice, which she calls The Lexicon Practice. The TLDR version: First you start a collection of words that you like. Second, you create “word banks” for specific pieces of writing.

The words don’t have to be fancy — in fact, it might be better if they aren’t fancy or exotic words that only a few people would recognize. What’s important is that they matter to you. Writing down the definitions of words that you like will help you figure out why they matter. (It also improves your vocabulary.) And don’t forget etymology. I use this website all the time. Learning the history of a word can open your mind to the possibility of metaphor.

After a few years with my word notebook, I started to write down phrases as well as individual words. Recent entries:

“Technical debt”

“Signal loss”

I don’t know how I’m going to use these phrases yet, or if I will ever make use of them at all, beyond writing them down in a notebook. (Though I guess I’ve “used” them by writing them in this post, which poses the question of what does it mean to “use” a word, anyway? Does a word have a sell-by date? Are there instructions? Must you use as directed so as to avoid mishaps, embarrassment, loss of livelihood, or carnage? But I digress.)

Have I told you that I'm in an MFA program now? It’s a strange time to enter academia. An hour from now, I will attend an emergency meeting in light of recent events. “Recent events” is probably not the kind of phrase that Gianni Rodari had in mind when he came up with his fantastic binomials, but that doesn’t mean the phrase is not without its creative potential. I remember another September, almost a quarter of a century ago, when I lived in Brooklyn. After the terrorists attacked, many things were blamed on “recent events.” But there was this one ATM machine, at a Citibank in downtown Manhattan, that had a sign telling people that it was offline “due to the events of last Tuesday.” I used to walk by it every day, between the subway station and my job at a literary agency on Bleecker Street. The sign was up for so long that the paper got gray and tattered, and the ink blurred with rain. Finally, they took it down.

Other interesting things

I bought Telephone Tales immediately upon finishing “The Italian Genius Who Mixed Marxism and Children’s Literature” by the inimitable Joan Acocella. It was one of the last pieces she contributed to the New Yorker before her death in 2024. Every time I open a new issue of the New Yorker, I miss seeing Acocella’s name. If you are interested in critical essays that crackle with intelligence while also managing to entertain and surprise, you could do worse than to pick up a copy of The Bloodied Nightgown and Other Essays.

If we spoke Old English, we would use word compounds with figurative meanings, such as “whale-road” for sea or “day-count” for life. Here is a list of kennings.

Thanks to my fellow Austinite, Austin Kleon, for posting this excerpt of Joy Williams’ essay, “Autumn.” (While we’re on the topic of word choice, consider the word “darkening” in the paragraph below. What if she had written “dark” instead?)

Fall is. It always comes round, with its lovely patience. If in the beginning it’s restless, at the end it’s resigned, complete in its waiting, complete in the utter correctness of what it has to tell us. Which is that we’re transitory. We’re transient, we’re temporary, we’re all only sometime. We will pass and someone else will take our place. Our pursuit of living founders each time we remember this. Fall is the darkening window, the one Hart Crane had in mind in his poem “Fear,” the window on which licks the night.

It is more than refreshing, it is healing, to read your writing. Yoo always hit a familiar note. My senior thesis began with the words "wavenoise," so moved was I by Joyce's words. Michelle

Recently learned and added:

Drey: a squirrel nest

Kettling: birds swirling together in an updraft