Once again, the specter of Lauren Groff haunts my writing life. Her new novel, The Vaster Wilds, came out this fall, so I have found her in several places lately, including a profile in the New York Times magazine, and an episode of my favorite book podcast, otherppl with Brad Listi. Every piece about Lauren Groff seems to focus on her self-discipline and productivity. This is often the case when writers interview other, more prolific writers: on one side of the discussion you have a journalist or a moderately successful novelist, and on the other side you have a 45-year-old woman who has written two short-story collections and five novels, two of which were National Book Award finalists. Oh, and also she is married and has two kids.

When she married, Lauren Groff reportedly made an agreement with her husband that the mornings would always be her writing time. When the couple had children, Groff’s writing hours remained inviolable—an “immovable boulder”—while Mr. Groff took care of waking up, feeding, and shepherding their two children through the activities of the earlier part of the day. I can’t remember where I first read about this arrangement, but it stuck with me. The phrase “immovable boulder” came up often in my therapy sessions. I wished that I had had the guts and the vision to have entered into an agreement about my writing schedule when I got married. But that would have required a knowledge of myself that I didn’t have when I got married at 28, or had my first child at 32. I couldn’t have known back then that I would want to write so badly in my 40s that I would stop practicing law and rearrange my whole life.

At one time, Lauren Groff refused to answer questions about balancing motherhood with writing. According to Huffpost:

The interviewer asked Groff, a mother of two who spent the last ten years producing three novels and two short story collections, about her “process” and how she juggles it all.

Groff replied: “I understand that this is a question of vital importance to many people, particularly to other mothers who are artists trying to get their work done, and know that I feel for everyone in the struggle. But until I see a male writer asked this question, I’m going to respectfully decline to answer it.”

I admire this position. But as another mother trying to get her work done, I am also grateful that Groff seems to have relaxed her stance against work-life-balance questions in recent years. I want to know how she does it, and clearly I am not alone. The publicity around her new book goes in the opposite direction: focusing on her intimidating process almost to the exclusion of other topics. We learn about her early morning writing schedule, her many handwritten (and then discarded!) drafts, the two-hour-long runs.

In the interview with Brad Listi, we hear that Groff reads 300 books a year and keeps a spreadsheet of what she reads. Now, I also read a lot and keep a spreadsheet. (Actually I keep four spreadsheets: books, short stories, essays, and poems.) But Groff is reading almost a book a day. This stat gave me pause. Did I hear correctly that she listens to a four-hour audiobook during a two-hour run? Listi was so impressed with the length of her daily workout, he failed to examine the fact that she is listening to audiobooks at 2X speed. Yuck!

Audiobooks: a digression

Hello, my name is Sarah and I am an audiobook addict. I fully endorse audiobooks for the pragmatic reason that I would never be able to finish as many books as I do without them. It is the only way to read while you do other things with your hands! (While I have heard that Toni Morrison used to read while driving a car, I cannot find any evidence of this rumor and do not recommend it as a life hack unless you want to literally hack up your life.) But I also listen to audiobooks because I enjoy the experience. I am skeptical about the pleasure factor in hearing a chipmunk shout narrative into your ears while you sweat.

My husband listens to certain nonfiction books at 1.5X speed. Whatever. He’s from Pennsylvania. To me, a Texan for whom fast talking is a microaggression, listening to books at 2X speed is psychotic. On my public library audiobook app at this moment are two masterpieces: The Bluest Eye, read by Toni Morrison, and Middlemarch, read by Wanda McCaddon, a delightful actress whose impression of provincial English gentlemen cracks me up while I’m out walking the dog. (I’m dying for one of my neighbors to ask me why I’m laughing.) I want to savor listening to these books, not power-listen through them. I suspect that Groff speeds through books she wants to have read versus books she actually wants to read. If I ever get to interview, her, I will ask her how she decides what speed to listen to a particular book.

I used to envy people like Groff, who always knew that she wanted to write. I’m over that now. Recently, a younger friend of mine asked me how I’d learned to stop regretting the past. I didn’t know until I answered her question: I wrote about it.

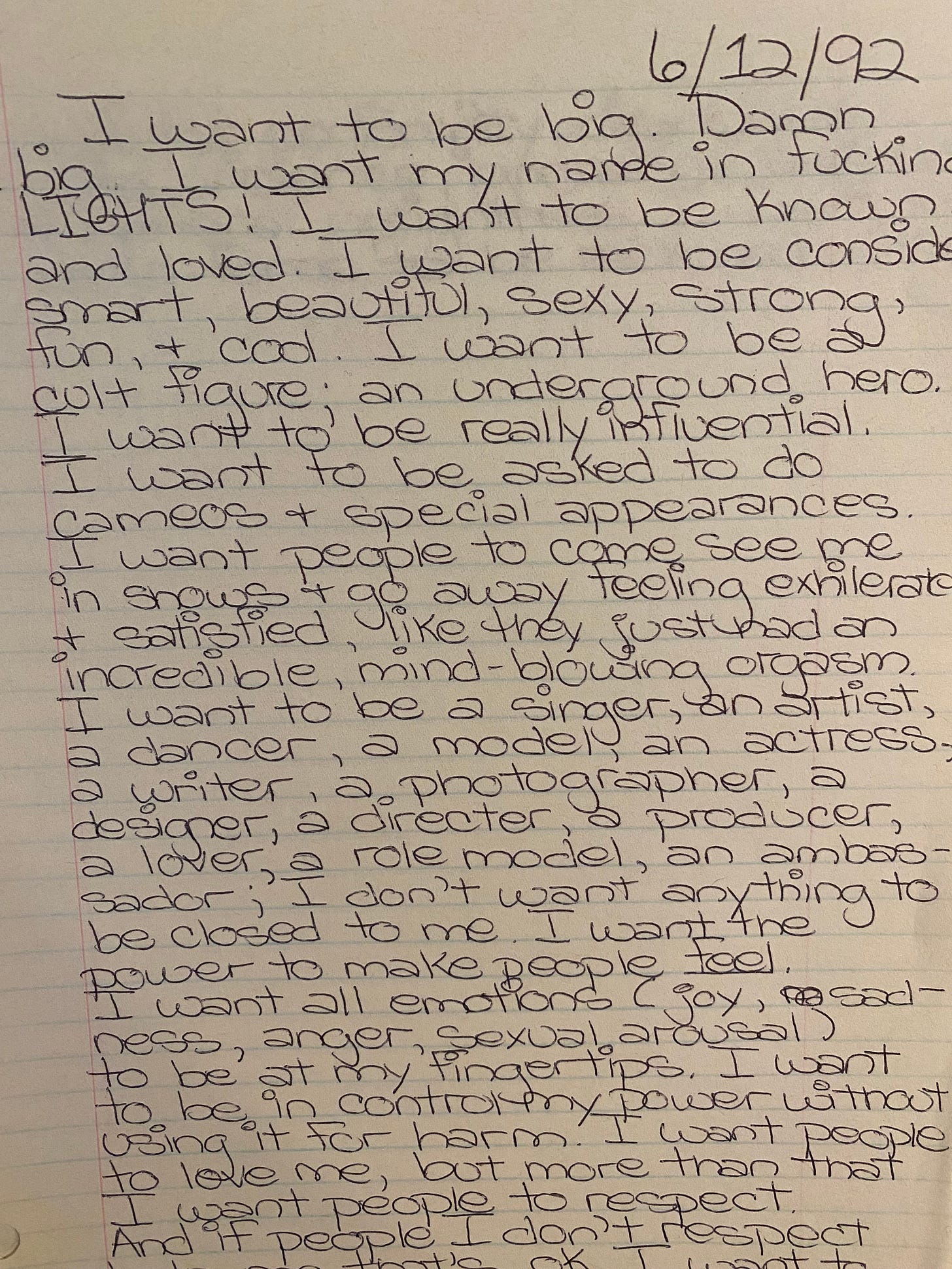

In my early 40s, I couldn’t sleep. I used to twist my mind at night like a wet washcloth, trying to wring out some explanation for how I had become this overworked, stressed-out mom, always trying to make myself smaller, when I had once been the 14-year-old girl who wrote in her journal: I want to be big. Damn big. I want my name in fucking lights!

It gets even cringier from there.

What happened when I read my old journals is a longer story and the subject of my still-in-progress memoir. One offshoot of that journey was that I sat down and wrote about every job I’ve had since I was a teenager. In writing “Quitter,” I discovered that I had always been a writer. I saw that everything I’d done in the past had led to who I am now: a woman with the desire and discipline to write, as well as a lifetime of events, people, and experiences to write about.

So I’m not like Lauren Groff. I didn’t know that I wanted to be a professional writer in my twenties and pursue that goal with relentless dedication. But that doesn’t mean any of my time was wasted.

Now I can read about Lauren Groff and other writers with lifelong, admirable writing practices without envy. A writing schedule is a wonderful thing to develop. In the words of Annie Dillard, a schedule “defends from chaos and whim.” It is a “scaffolding on which a worker can stand and labor with both hands at sections of time.” An immutable schedule, an early dedication, good mentors, a room of one’s own, premarital agreements—all of these things are important, but they are also just tools in the writer’s kit. What matters most, it seems to me, is the writer’s attention to the work in front of her right this second.

How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives. What we do with this hour, and that one, is what we are doing.

— Annie Dillard, The Writing Life

Other interesting things

In this video, Groff talks about her previous novel, Matrix, which originated when she learned about 12th century nun and poet Marie de France in college. Fast forward to the 15 minute mark to hear her stunning advice to the undergraduates in the audience: “There are things that you are going to learn about now that you will carry with you as friends for the rest of your lives . . . You will be host to these elements that you will just love forever.”

I love “Annunciation,” a short story that reads like memoir. Read if you enjoy stories about writing, running long distances, and the people you meet in youth hostels. “In the bathroom, I stared at my face in the mirror, trying to see if the new person I was becoming was someone who would have a threesome on the floor with Brazilians so beautiful it was hard to see their faces for their glow. I decided that I would instead be a person shivering in her pajamas on the disgusting puce couch in the common room. I regret this decision, as I regret all the times in my life that I turned away from living.”

And the winner for the best NYT By the Book goes to, you guessed it, Lauren Groff. Notable quote:

When male writers list books they love or have been influenced by — as in this very column, week after week — why does it almost always seem as though they have only read one or two women in their lives? [. . .] Something invisible and pernicious seems to be preventing even good literary men from either reaching for books with women’s names on the spines, or from summoning women’s books to mind when asked to list their influences. I wonder what such a thing could possibly be.

Bye for now,

S.

p.s. You are reading The Compendium, an occasional newsletter about reading and writing from Sarah Orman. I’m also on Twitter and Instagram.