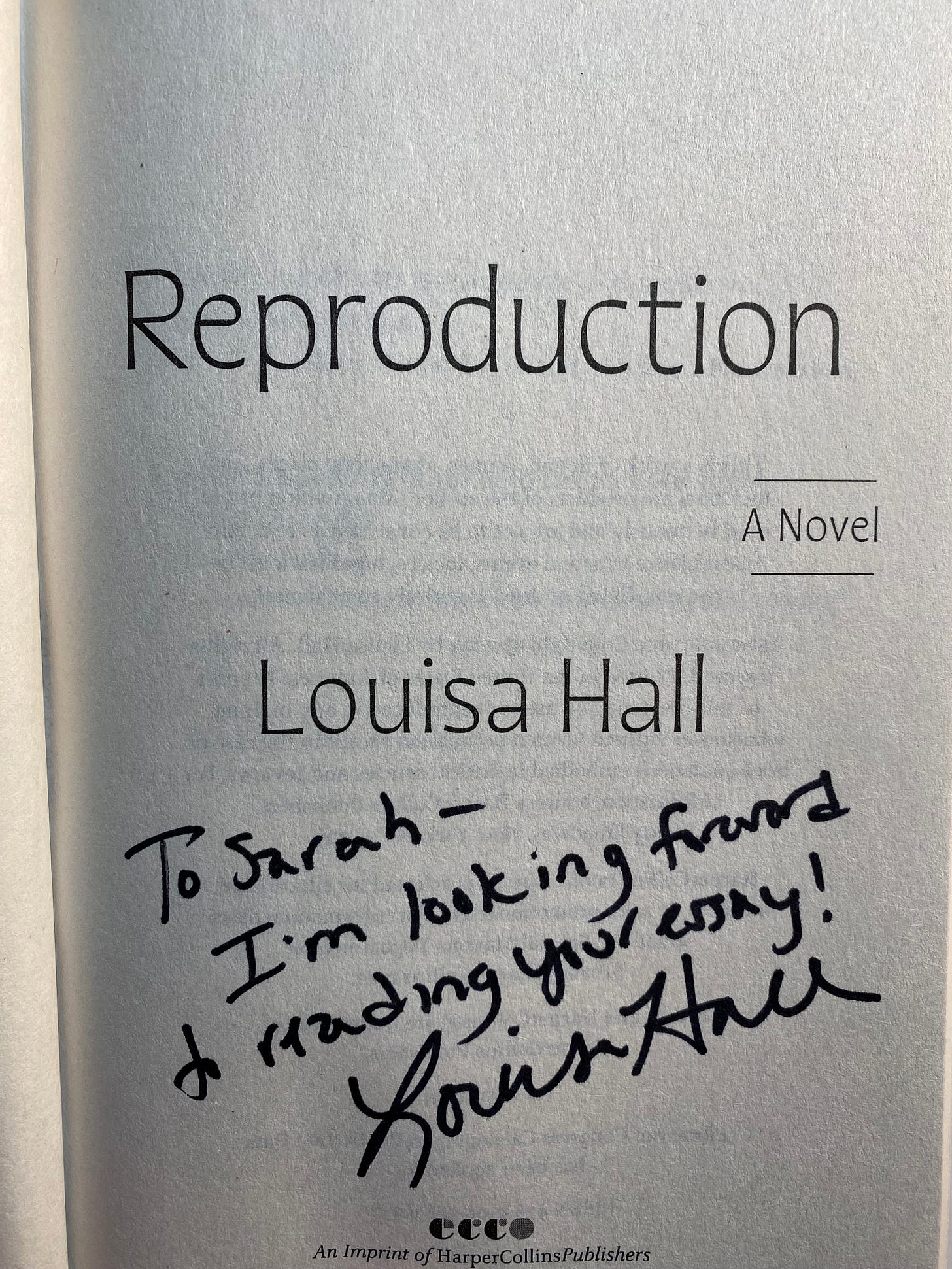

It’s the weekend of the Texas Book Festival, one of my favorite times of year in Austin.* Amanda Ward, a bestselling novelist and a mentor of mine, calls the TBF “ACL for writers,” and she has a point. In the days leading up to this weekend, my friends and I strategized like teenagers hoping to see all the biggest acts at a music festival. I didn’t make it to see Ann Patchett or Roxane Gay. For me, the one must-see event of the TBF was a panel called “The Monstrosity of Motherhood,” described as “a poignant conversation about the darker sides of motherhood” as seen in three recent novels: Reproduction by Luisa Hall, The Nursery by Szilvia Molnar, and Cutting Teeth by Chandler Baker.

I have long argued that horror is the perfect genre for stories about motherhood. Shape shifter, werewolf, vampire, zombie, ghost—during my early days as a mother, I was all of these at one time or another. And if it wasn’t me, it was my baby. Especially the first one, my son, who turned 15 last week. He’s fine now, but when he was an infant and our nights together consisted of my attempts to breastfeed and his prodigious reflux, I definitely felt like a character in a dark and sinister plot.

At the time, I was pretty sure that I was the first person to identify a link between the eerie world of horror and the new world I was learning to navigate—a world in which I was never fully awake or fully asleep and could not be more than arm’s length away from my baby without terror, confusion, and disorientation. Of course I’d read a stack of parenting manuals, but What To Expect When You’re Expecting had not prepared me for this massive shift in identity, which was a problem.

Reading about a thing is how I learn to think about it. I needed to learn how to think about this weird liminal state in which my baby and I were trapped. Where would I find my experience reflected in literature?

In recent years, novelists have embraced horror as a genre for telling stories about domesticity.** See, for example, Rachel Yoder’s Nightbitch, in which a working mother becomes convinced that she’s turning into a dog. Or Szilvia Molnar’s The Nursery, about which Claire Dederer wrote in the New York Times Book Review:

“The Nursery concerns itself with something every new mother goes through: the discovery that she’s gone from being a (relatively) free entity roaming the earth to a bleeding, exhausted body that exists mostly to nurture her baby. [ . . .] Home from the hospital, charged with the care of this small creature, the narrator is unrecognizable to herself. Space, time and identity are altered. She’s not taking it well. She tells us on the first page: ‘The baby I hold in my arms is a leech, let’s call her Button.’”

I wish that novels like Nightbitch and The Nursery had been around in 2008, when I became a mother. I don’t remember reading a story that expressed the terror I felt as a new mother until 2018, when I read Karen Russell’s short story, “Orange World.”

In “Orange World” (now part of Orange World and Other Stories) a demon promises a pregnant woman who has received some scary test results that she will give birth to a healthy baby if she agrees to feed him. The demonic nursing scenes are not metaphorical:

“It lays its triangular head on her collarbone, using its thin-fingered paws to squeeze milk from her left breast into its hairy snout. Its tail curls around her waist. Unlike her son, the devil has dozens of irregular teeth, fanged and broken, in three rows; some lie flat against the gums, like bright arrowheads in green mud. Its lips make a cold collar around her nipple. She feels the tugging deep in her groin, a menstrual aching. Milk gushes out of her, more milk than it seems any single body could possibly produce; more milk, she’s sure, than her baby ever gets.”

When the woman in “Orange World” lay on her side in a wet Portland gutter to breastfeed a greedy little demon, my breasts ached although my body hadn’t been a source of food in years. I felt delighted. Because now I knew that I wasn’t alone in thinking about motherhood in terms of horror stories.

Then I found Shirley Jackson.

Reader, no doubt you’ve heard of Ms. Jackson, author of the notorious short story, “The Lottery,” which still holds the record for prompting the most letters to the editors of The New Yorker. If there had been an internet in 1948, we would have said that “The Lottery” broke it.

Shirley Jackson was also a cartoonist.

Last summer, I went on a bit of a Shirley Jackson binge. I read the two novels widely considered to be her masterpieces, The Haunting of Hill House and We Have Always Lived in the Castle. Then I read Ruth Franklin’s award-winning 2017 biography, Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, in which I learned that The New Yorker probably wouldn’t have received so many letters about “The Lottery” if the magazine had distinguished between factual articles and fiction in 1948. (!) I also read The Letters of Shirley Jackson, a compilation of the writer’s correspondence, edited by her son.

There are a lot of things that I want to say about this reading adventure. If you have spent more than a minute in my presence in the last six months, chances are you have heard me say some of them. Here, I want to focus on one thing in particular:

Jackson didn’t just write creepy, critically acclaimed books, she also wrote charming and funny essays about her life at home with her four children and literary critic husband, who, in the way of men in that generation, may be identified as child #5.

At the time, people didn’t know how to interpret Jackson’s genre straddling. Was she a serious literary author? Or was she one of the “happy housewife heroines,” the women writers Betty Friedan accused of pandering to the patriarchy in the pages of women’s magazines like Good Housekeeping and McCall’s?

There is a practical side to this question. Jackson wrote pieces for women’s magazines for the money—she was the primary breadwinner for her family—and struggled with the marketing of her work, as when one of her essays about motherhood was included in a book with a silly cover. But I see no contradiction between the themes that dominated Jackson’s creative life. Motherhood is scary.

Specifically, American motherhood is scary. The three novels featured on the “Monstrosity of Motherhood” panel I saw yesterday cover topics such as childbirth, infertility, miscarriage, postpartum depression, sleep deprivation, breastfeeding, loss of identity, fear of school shootings, and more. How much harder is it to survive these problems in a capitalist system that devalues the work of caretaking and fails to support working families? In some ways, motherhood is even scarier in 2023. Listening to these authors discuss their work yesterday, it was impossible to forget that we were sitting in a tent outside the Texas Capitol, where lawmakers have systematically chipped away at the right to reproductive healthcare for years while also failing to address our state’s pitifully high rate of maternal mortality.

I have more to say about horror, Shirley Jackson, and motherhood, but as this post is already crazy long I will probably have to save them for a more formal essay. For now, consider the women in four Texas counties who cannot legally travel out of state to seek an abortion. That is truly horrific.

Other interesting things

I am intrigued by A Haunting on The Hill, an authorized sequel to The Haunting of Hill House by Elizabeth Hand, whose novel, Hokalua Road, I enjoyed earlier this year. Hand’s essay in The Guardian suggests that she would agree with my theory that Jackson’s fiction and nonfiction share the common theme of a woman at home, trying not to disintegrate. “Houses aren’t safe spaces in Shirley Jackson’s fiction.”

Check out Frankenstein’s monster’s reading list.

We know that Carmen Maria Machado is into Shirley Jackson because her Substack newsletter is called Cup of Stars. In this interview in The Atlantic, Machado explains why she loves the scene in The Haunting of Hill House where Eleanor sees a little girl who wants her cup of stars.

“Don’t do it, Eleanor told the little girl; insist on your cup of stars; once they have trapped you into being like everyone else you will never see your cup of stars again; don’t do it; and the little girl glanced at her, and smiled a little subtle, dimpling, wholly comprehending smile, and shook her head stubbornly at the glass.”

Bye for now!

S.

*Lest you think I have nothing nice to say about Republicans, let it be known that we have Laura Bush to thank for the Texas Book Festival! I am always reminding people that the former First Librarian is the reason readers and writers get to take over the Capitol for two days a year. Credit where credit is due.

**I found this Times Book Review headline vaguely snarky. Is it just me?

It will be a while, but I have an essay coming out in an anthology on the lure of psychosis during my intro to postpartum sleep deprivation. Early motherhood--in modern day life--is indeed horror.