Percival Everett is a fox

The author of James, Erasure, and about 30 other books (not even counting books within books) and the fox/hedgehog dichotomy.

In the most famous essay from his book, Russian Thinkers, philosopher Isaiah Berlin divided writers into two categories: hedgehogs and foxes. This pairing comes from a line by the Greek poet Archilochus: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.” In Berlin’s formulation, hedgehogs “relate everything to a single central vision, one system less or more coherent or articulate, in terms of which alone all that they are and say has significance.” In contrast, the foxes “pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory.”

According to Berlin, foxy writers and thinkers

lead lives, perform acts, and entertain ideas that are centrifugal rather than centripetal, their thought is scattered and diffused, moving on many levels, seizing upon the essence of a vast variety of experiences and objects for what they are in themselves, without consciously or unconsciously, seeking to fit them into, or exclude them from, any one unchanging, all-embracing, sometimes self-contradictory and incomplete, at times, fanatical, unitary inner vision.

A few days ago, my husband and daughter were their way to school when my daughter texted me: “We saw a FOX!” After school, I asked where they saw the fox and she said, in the tone of a newly minted teenager: “It was in the same place where we saw the sheep.” She was referring to an incident that happened last spring, when she was 12. We were driving home from school when she suddenly yelled: “SHEEP!” At first I thought she was just tapping into whatever frequency inspires her to randomly say “Monkey!” or “Potato!” But no. I looked in the direction she was pointing and saw an actual sheep near the train tracks. The sheep was eating grass. It looked unimpressed by the precarity of its situation. My daughter called 311, and the operator was as nonplussed as the sheep. They typed in whatever code they use for “sheep by the highway,” and we all went on with our day. But to me, these wildlife sightings felt like an omen.

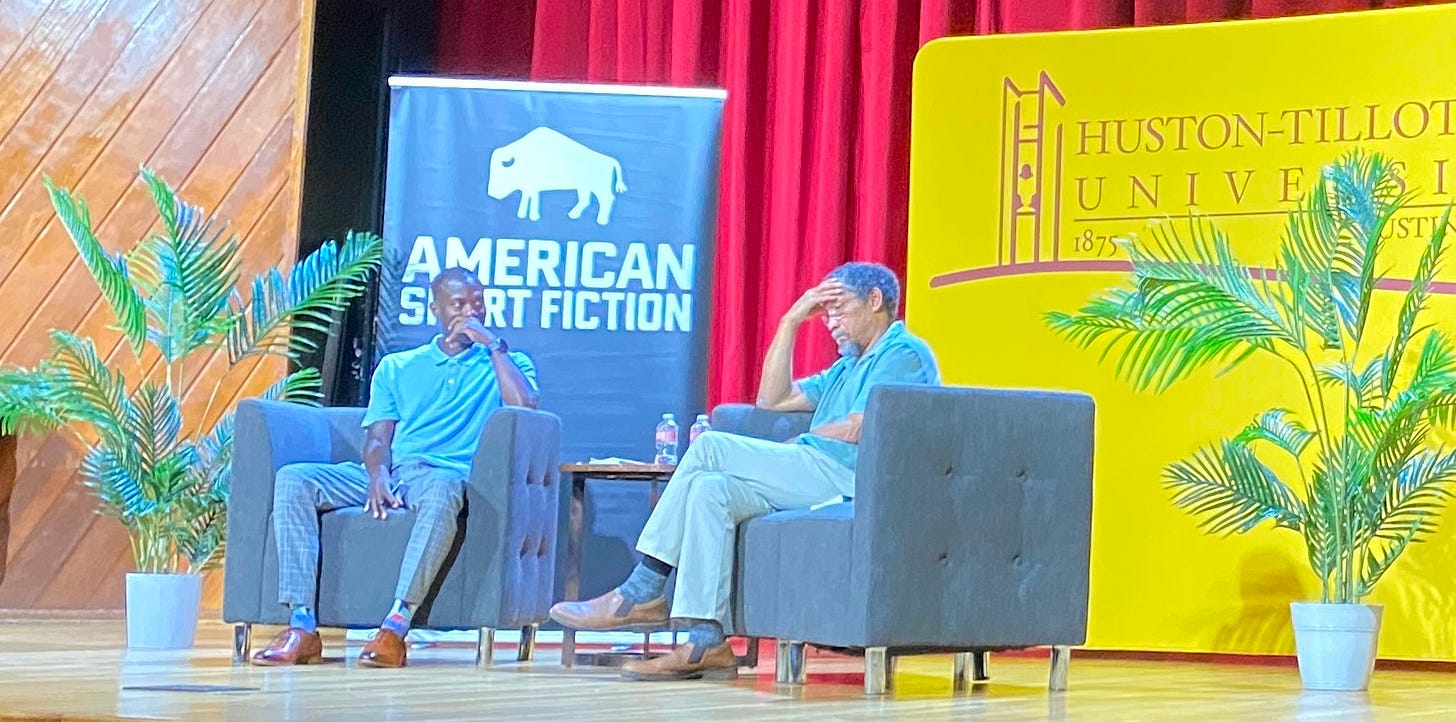

Last month, I saw Percival Everett speak at an event hosted by American Short Fiction at Huston-Tillotson University. Everett appeared on stage with Roger Reeves, an award-winning poet and literature professor at the University of Texas. The two men sat in the standard arrangement for a public literary conversation: two armchairs angled towards each other.

Like a fox, my ears perked up when Reeves alluded to Berlin’s famous essay. Percival Everett, said Reeves, is a fox, “leaping from form to form.” Suddenly everything fell into place. I knew why the fox showed up in my neighborhood. Clearly, it was the spirit of Isaiah Berlin urging me to write about Percival Everett.

The Percival Everett Zeitgeist

Percival Everett is a novelist, poet, short story writer, and college professor who lives in California. Recently, Everett’s name has catapulted into prominence, which can be attributed to James, a retelling of Huckleberry Finn through the perspective of Jim that is a finalist for the 2024 National Book Award, and the Oscar-winning movie American Fiction, adapted from Everett’s novel, Erasure.

Last summer, I saw Everett’s longtime publisher, Carmen Gimenez, the executive director of Graywolf Press, give the keynote speech at a writer’s conference. “We’re living through a Percival Everett zeitgest,” she said. “But at Graywolf, we’ve always known he was a genius.” With the support of Graywolf Press, a small publisher, Everett has been writing and publishing novels, short story collections, poetry, and nearly uncategorizable mock historical records (see: A History of the African-American People [Proposed] by Strom Thurmond) for decades.

Everett’s career in publishing is an example of the perils of being a fox. Had he been published by one of the Big 5 publishers, it’s unlikely he would have been supported through so many different forms. He doesn’t care to linger in one genre for too long. He has described his agent begging him to try, just once, and repeat himself. “I’ve been called a Southern writer, a Western writer, an experimental writer, a mystery writer, and I find it all kind of silly,” he said in 2021. “I write fiction.”

I’ve read three of Everett’s novels, James, Erasure, and The Trees, a very dark and (if you can imagine) funny crime novel about the legacy of lynching. Each novel was dazzling, hilarious, challenging and heartbreaking. Each was about race, America, and language. They were full of big ideas, and also they were page-turners. These were books I wanted to talk with someone else about, the kind of books that made me feel like I would read anything from the author’s mind.

Here are some of the topics that I noticed while perusing a selection of Everett’s novels: the art world; crime; fly fishing; politics; American history; academia; religion; publishing; literary theory; semiotics; corporate governance; math; astrophysics; geology; grief; horse training.

As I said, I’ve only read three of Everett’s books. I’m currently reading Watershed, a novel about a fly-fishing hydrologist who becomes embroiled in a dispute over Native American water rights. I’m hardly an expert on Everett, but I do know a few things about foxy writers. And even though “their thought is scattered and diffused, moving on many levels,” these writers usually have some themes that they come back to again and again. In Everett’s case, his work is preoccupied with language. Word play and misunderstandings abound. As in nonsense poetry (which he writes) and absurdism, the insufficiency of language is a frequent source of humor. Everett also uses language to illustrate the “badges and incidents” of slavery that the Thirteenth Amendment supposedly prohibited.

The narrator of James is the enslaved character known as Jim in Mark Twain’s novel. In Huckleberry Finn, Jim is a superstitious child in a man’s body. Everett restores this character to his full name and gives him an adult intellect to go with it.

If you’ve heard anything about James, you’re probably aware that James and the other enslaved characters speak standard American English. In the novel, enslaved characters only use the tortured vernacular of Jim in Mark Twain’s novel when they talk to white people. This is not intended as some kind of fantastical conceit. In a recent podcast interview, Everett described listening to an old WPA recording in which formerly enslaved people speak just like he speaks now. The “slave speech” from old books and movies, says Everett, is a myth. On the other hand, I don’t think his only goal in rewriting James was to make him sound more realistic. As Everett tells the podcast interviewer: “Any oppressed people will find a way of speaking and communication that doesn’t allow the oppressor entry.”

“Any oppressed people will find a way of speaking and communication that doesn’t allow the oppressor entry.”

James is a great entry into Everett’s novels. It’s not only a deeply thoughtful and thought-provoking book, it’s also a ripping yarn, with passages that rival Twain in adventure and slapstick humor. It’s also less overtly theoretical than some of Everett’s novels—though we do read James’s imaginary dialogues with Voltaire and John Locke. I listened to the audiobook of James, which is great if you want to experience the full impact of the characters’ code switching. I hope that readers who enjoy James as much as I did won’t stop there.

If you enjoy the way Everett uses language in James, you’ll really love Erasure: the story of an intellectually driven, not very successful novelist named Thelonious “Monk” Ellison who carries out a prank on the publishing industry by writing My Pafology, a novel riddled with racial stereotypes, as a satire of another bestselling novel, We’s Lives in Da Ghetto, the work of a debut author whose research consisted of visiting some relatives in Harlem for a couple of days. When My Pafology becomes a huge hit, Monk must pose as his pseudonym, Stagg R. Leigh. Hilarity and calamity ensue.

The theme of language is so strong in this novel, it called to mind the profound question once posed by another Erasure: “How can I explain when there are few words I can use? How can I explain when words get broken?”

Erasure is not only a satire of the publishing industry but also a story about a family. The novel makes clear that Everett’s interest in language is much bigger than lampooning cultural stereotypes. He’s interested in how all people fail to communicate, even people in the same family. Monk says: “Anyone who speaks to members of his family knows that sharing a language does not mean you share the rules governing the use of that language. No matter what is said, something else is meant.” Put another way: “It’s incredible that a sentence is ever understood.”

A lot has been said about My Pafology, which is an entire Book Within a Book (BWAB), consisting of 63 pages and ten chapters (titled “Won,” “Too,” “Free,” “Fo,” etc.) But My Pafology is not the only BWAB in Erasure. There is an entire curriculum vitae. There is a conference paper, also an excerpt from Monk’s experimental novel, F/V, heavily footnoted and drawing on Roland Barthes’ semiotic theory of literature. Do you need to read and comprehend all of these internal texts in order to understand Erasure? I would say, try your best. I didn’t catch every reference to Barthes or even Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man, and I still feel enlightened and enlarged by this novel.

A word about BWABs

BWABs are quintessential foxy writer behavior. How else are you going to write about a zillion different things in a zillion different forms without occasionally creating a portmanteau of inner and outer text? (See my recent post about Helen deWitt for another example.)

When it comes to readers, BWABs are not for everyone. I have known highly intelligent readers who are categorically opposed to them. They will read the outer book but not the inner. I don’t judge. As in most things, my feelings about BWABs are: it depends.

I have loved certain novels—Possession by A.S. Byatt comes to mind—while letting my eyes scan helter-skelter over the italicized BWAB parts, in full awareness that I am probably skipping over the author’s favorite bits. (Sorry, Antonia: your poetry was so tedious and your plot was so good!) With Percival Everett, though, I don’t think I would dare.

I do hope that readers don’t skip My Pafology in an attempt to avoid racial discomfort. This part of Erasure is the best satire I’ve ever read. Yes, it is uncomfortable to read, but it is essential to the novel. (More essential, I would argue, than the excerpt of Monk’s experimental novel, which is blessedly short.) Reading for comfort has its place, but in my view it’s overrated. I like to seek out what Jia Tolentino called “the genuine pleasure of decentering in fiction.” In James, it is easy to laugh at the racist white slaveowners as if I am in on the joke. But when I read My Pafology, I recognize racist tropes from my own day and age. I can’t pretend like I’m in on the joke because I’m the target audience of the type of story that the BWAB so perfectly satirizes.

I feel like I’m drifting a bit, so I’m going to try to steer the raft back to the muddy riverbanks by returning to the event at Huston-Tillotson.

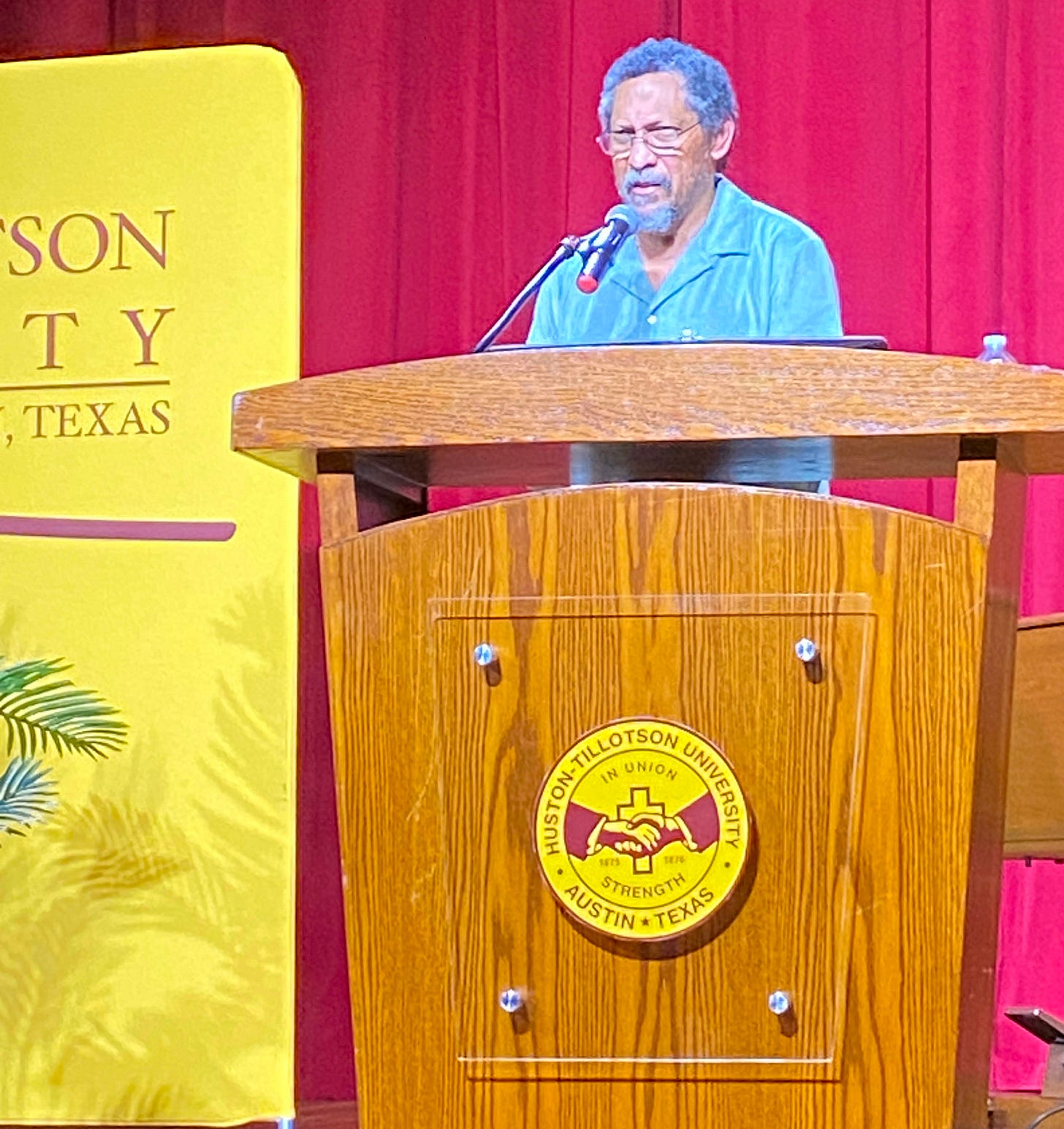

Before the discussion, Roger Reeves read a few poems, and then Everett went to the lecturn, supposedly to read from James. But he didn’t feel like reading. (Fox behavior!) Instead, he told a funny anecdote about working as a ranch hand in Wyoming many years ago. The anecdote culminated in a line of dialogue about false teeth that I won’t spoil here. Everett said this line ruined his life for twelve years because he kept trying to write it as a short story. As a young ranch hand in Wyoming, Everett recognized this brilliant sentence in the wild and thought it was a sheep by the railroad tracks, just waiting to be corralled into a pasture. But language had other ideas. It never wanted to be a short story, just a joke. The audience loved it.

Other interesting things

RIP Robert Coover, the recipient of a degree in Slavic studies in 1953 and author of a 2017 novel that imagined Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer in the Wild West. Coover described Huck Out West as inspired by Mark Twain’s own intended sequel, Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer Among the Indians. “It’s a very problematic work,” Coover said of Twain’s follow-up. “Very racist, very anti-Native American, and so on. So, I thought, ‘That has to be corrected.’”

On the occasion of Han Kang winning the Nobel Prize for literature, please enjoy this funny article in the New Republic about the “one big book” syndrome in publishing. “It’s difficult to believe now, but once upon a time—as recently as, like, 10 years ago—there used to be more than one book. Asking what it was like before there was one book is like asking what it was like when union density was high, or when you didn’t constantly receive push notifications from major media organizations about the Hawk Tuah girl signing with UTA. What was it like? All we have are our dim, corroded memories, and those aren’t doing us very much good because of all the Hawk Tuah girl push notifications. The lost world of more than one book feels hard to conjure.”

Here is a conversation between poet/video artist Claudia Rankine and gender theorist/philosopher Judith Butler about the power of white women’s tears. Rankine asks Butler, “What do you have to say for your people?” I first watched this after the Central Park birdwatcher incident in 2020, but I’m still thinking about it.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the father of modern neuroscience, had this to say about foxes: “To him who observes them from afar, it appears as though they are scattering and dissipating their energies, while in reality they are challenging and strengthening them.” What Howard Gruber called ‘networks of enterprises’, which I shall think of as ‘networks of foxiness’ henceforth.

I love these essays so much — I feel like they reverse the stupid that Hawk Tuah news makes me. I also have a fox living in my backyard.